Understanding Teenage Schizophrenia

The onset of schizophrenia can be a harrowing experience, both for those developing the condition and the people around them. Delusions, hallucinations, and general psychosis can be coupled with significant changes in personality, speech, and affect. Serious social and occupational dysfunction occur, and symptoms can persist for years.

These challenges are compounded when the one exhibiting early symptoms is a teenager. Not only are they still developing physically, they are rapidly changing socially and psychologically. The importance of adolescent connection and belonging is well documented, and schizophrenia can devastate already-fragile support networks.

Unfortunately, even among mental health caregivers, evidence suggests that there is a significant gap between scientific knowledge and clinical practice. This research underscores a need for community-wide education for all stakeholders – clinicians, community partners, and families.

This article provides an overview of effective schizophrenia treatment for teenagers and presents a discussion of different treatment modalities.

The Challenges of Adolescent Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia remains a prevalent and severe mental illness, impacting upward of 25 million individuals globally, and has gained public notoriety for its serious and often visible symptoms.

However, despite this prevalence, treating teen and adolescent schizophrenia poses significant challenges across a variety of domains. There are barriers to teen treatment in particular, with research often failing to assess basic questions around treatment efficacy – one meta-analysis highlights that “Cognition, functioning and quality of life, suicidal behaviour and mortality and services utilisation and cost-effectiveness were poorly covered.”

Further, multiple confounding factors make diagnosis and assessment more complex and unclear relative to adult cases.

Assessment and Diagnosis

Adolescents only make up a small proportion of those living with this disorder, with early-onset schizophrenia comprising only a fraction of overall cases. Indeed, most diagnoses for men occur in their early twenties, and most diagnoses for women even later – in their late twenties to early thirties.

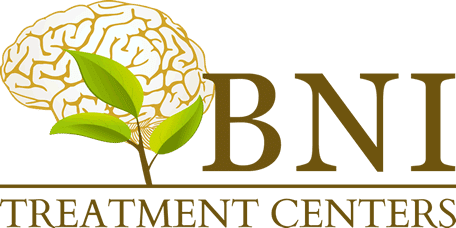

Additionally, roughly 8% of teenagers exhibit psychotic symptoms, independent of any diagnosis of schizophrenia or psychiatric disorders. Some of these symptoms can be chalked up to “teens being moody”, or other psychosocial developmental changes. Others are simply brushed to the side by oblivious parents.

Compounding this are opaque and amorphous DSM criteria. Many teens are then misdiagnosed with some combination of depression, bi-polar disorder, and episodic psychosis.

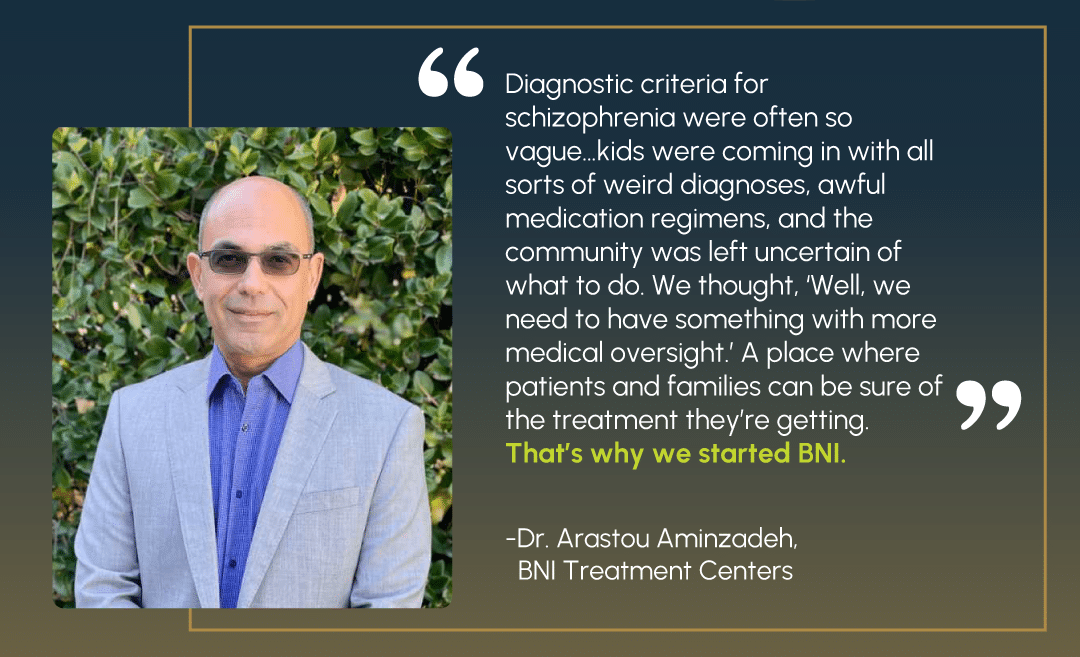

“One of the major challenges facing diagnosis is that all of the criteria are based on adult diagnostic studies,” says Dr. Arastou Aminzadeh, adjunct faculty at the UCLA Geffen School of Medicine and chief medical officer at BNI. “We have to extrapolate from that. At the same time, when it comes to psychosis in teens, it’s way more common. Some of them may even be developmentally appropriate.”

An example Dr. Aminzadeh highlights is that of an imaginary friend, which while appropriate for a young child, may suddenly be cause for concern at an older age.

“Largely, what we see is that many practitioners and diagnosticians get stuck on these hallucinations, and don’t do a full evaluation for what is happening. Many teens may be put on antipsychotics who don’t need them, as the underlying cause is PTSD or another affective disorder, not schizophrenia.”

This further muddies the waters, leading to confusion in both clinical practice and research.

Additional Risk Factors

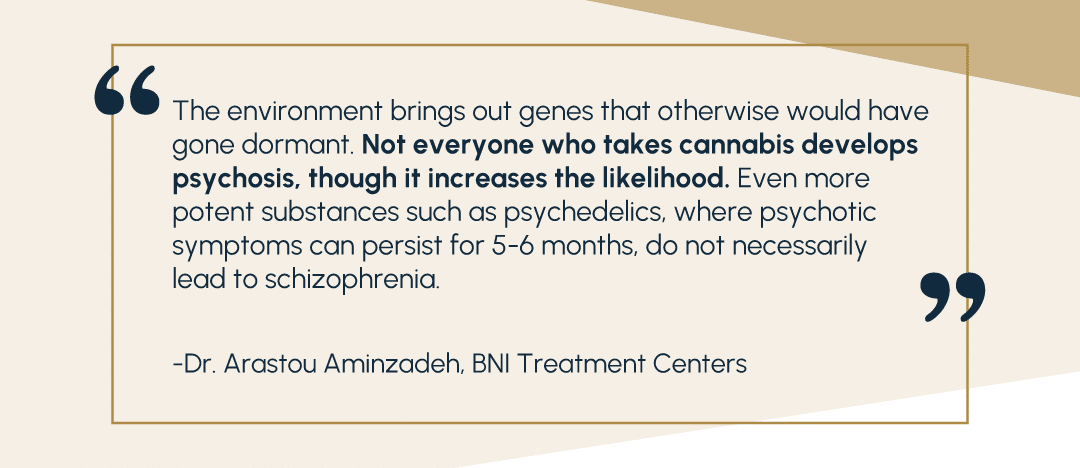

Close family psychiatric history remains one of the primary predictors of schizophrenia. This is due in part to genetic components, but also environmental exposure to the stressors of living with mental illness. The teenage population is particularly vulnerable to these and other outside risk factors. Though more work needs to be done in the space before conclusions can be drawn, a variety of links are becoming apparent.

First, marijuana and substance use disorders. In 2023, a study found significant links between marijuana use disorder and schizophrenia. These links were profound, suggesting that up to 30% of their sample cases of schizophrenia in young males could have been prevented by averting cannabis use disorder as teenagers. This highlights the importance of a multi-disciplinary approach to schizophrenia treatment and recovery, both in preventative and clinical treatment stages.

Additionally, other psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder are strongly linked with schizophrenia. Evidence suggests that these disorders can predict future episodes of psychosis and schizophrenia. Indeed, this research found that 50% of all diagnosed cases of psychosis and schizophrenia had, at some point, been enrolled in childhood or adolescent mental health services. More research is needed to determine if this can lead to preventative and ameliorative treatments.

Finally, today’s teens are in a unique position to experience potential triggers of schizophrenia. Stressful life events often act as catalysts for early-onset symptoms, with negative emotions and social isolation being driving factors. Unfortunately, in recent years teens have experienced sharply increased feelings of social isolation and loneliness. Many of these feelings have only worsened since the COVID lockdowns. While no causal link has been confirmed, the increased exposure to potentially inciting events places teens and adolescents at specific risk.

The Importance of Multidisciplinary Treatment

When asked about the benefits of multidisciplinary treatment, Dr. Aminzadeh’s answer was direct.

“It’s crucial,” he said bluntly. “That’s why we need a full team. A primary therapist, a family therapist. Education, long-term care, and designing preventive measures moving forward. It all matters, in every discipline.”

Schizophrenia’s many complex, chronic, and chaotic symptoms lead to complications in day-to-day functioning. For many patients and their families, this is a disabling and disruptive disorder, and prognoses seem pessimistic at best. However, despite its reputation as a life-long illness, many patients find that treatment makes a significant impact – a recent meta-study suggests that a majority of individuals can see moderate improvement, with nearly one in four able to achieve complete recovery.

Critically, the study echoes the lack of clinical development, with highly inconsistent levels of treatment and goal-setting, “despite more than 100 years of research”. For example, it finds that treatment in North America led to significantly worse results than in European nations – 36.4% of North American patients had “moderate” recovery, compared to 63.4% of Europeans.

Dr. Aminzadeh explains, “Outcomes vary widely based on the patient,” he said, “In parts of Europe and other areas with high recovery outcomes, if someone has schizophrenia, they receive a much more comprehensive treatment plan. Their skills and abilities are assessed, and they are plugged into a place in the community. Those around them can help monitor their treatment compliance and progress.”

He contrasted that to the United States, “Here, we often treat schizophrenia as episodic. A crisis occurs and the person with schizophrenia surfaces. They get immediate treatment, and then are sent to outpatient care. And most of the time, because of the nature of their illness, they fall out of this process.”

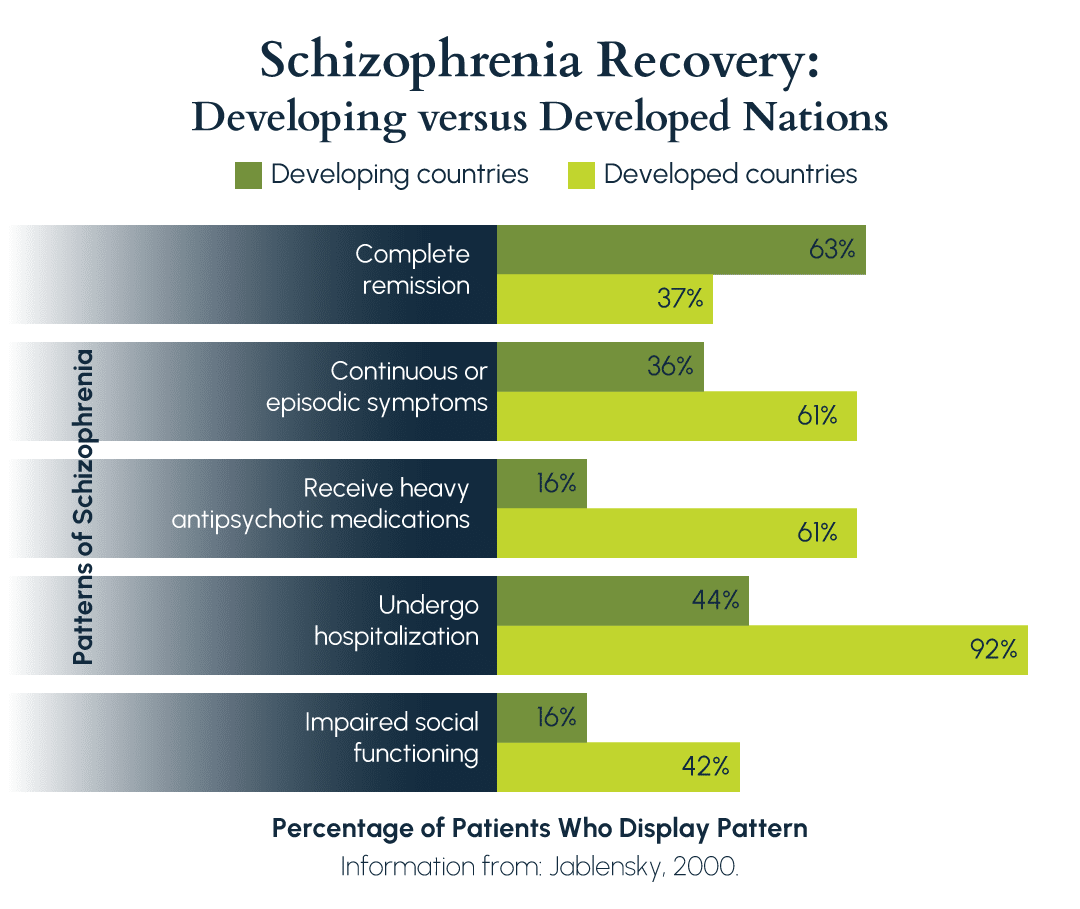

In a study from 2000, outcomes were significantly improved in developing nations.

Indeed, this pattern has repeated itself, with developing nations having better recovery outcomes than their developed counterparts. Instead of an approach dominated by medical and behavioral interventions, families in high-recovery cultures surround and support those with schizophrenia, with an emphasis on reintegration into society. Expectations for recovery are higher, and support is broader in scope and more persistent.

Effective schizophrenia treatment involves a recognition of this long-term journey back to recovery. It involves not only a set of pharmacological aids, such as antipsychotics and mood stabilizers, but also skill development and rehabilitation components. Cognitive-behavioral therapies will emphasize these areas, and functional life skills training has been shown to improve outcomes.

The journey to a self-sufficient life requires an in-depth and multifaceted approach, involving psychiatrists and support networks at every step. And indeed, research shows time and time again that those who receive multi-disciplinary treatment for schizophrenia have improved outcomes.

Pharmacological Treatments

Broadly speaking, pharmacological treatments fall into three categories: antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers. Supplemental medications may be administered to manage side effects or other health conditions. While each has its role, their interactions are often complex and difficult to predict. Trained psychiatrists must be involved with the client at the outset of treatment and continuously throughout.

Antipsychotics

These are often an integral part of schizophrenia treatment, enabling clients to reduce symptoms of psychosis. Hallucinations, delusions, and disordered thinking can be significantly reduced through effective antipsychotic interventions. These are generally separated into second-generation – or atypical – and first-generation – or typical – antipsychotic agents.

Of the two, atypical agents are generally considered more effective. This is because they not only treat a wide array of psychotic symptoms, but they also can have positive impacts on things like mood, suicidality, and depression. One of these atypical agents, clozapine, is particularly effective at reducing suicidal ideation and other symptoms of psychosis. For those patients who have been resistant to other atypical or typical treatments, clozapine can often help mitigate symptoms. However, it is generally not the first option of treatment, as it comes with significant health risks, such as agranulocytosis, a dangerous reduction in white blood cell count.

Attempts to find a specific generalized treatment plan, such as the Texas Medication Algorithm Project, have been met with mixed results, underscoring the importance of an individualized approach to antipsychotics and schizophrenia treatment.

Antidepressants

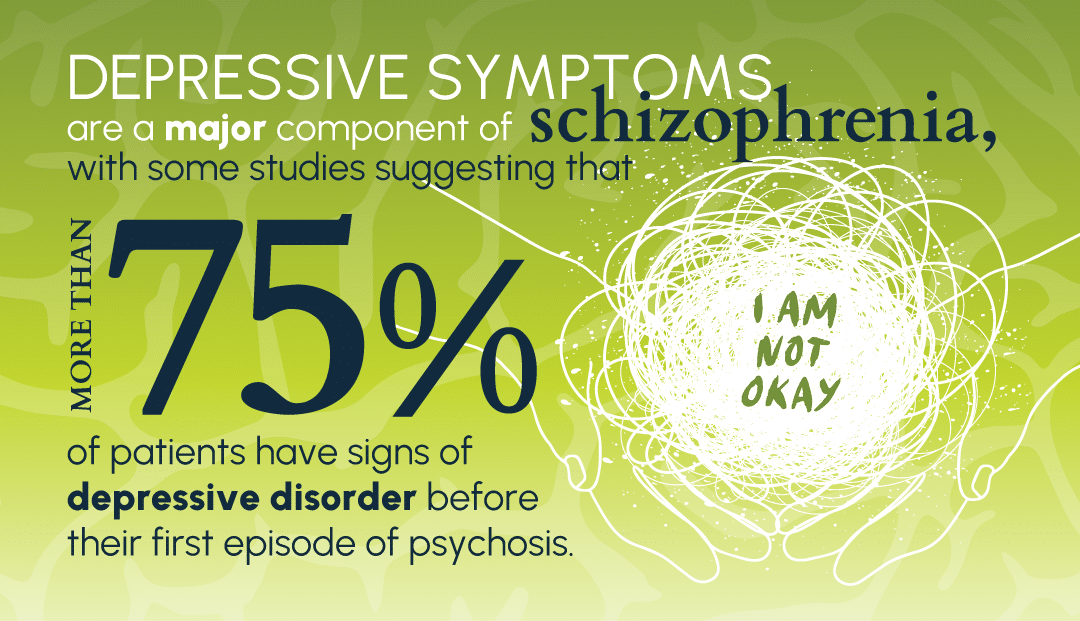

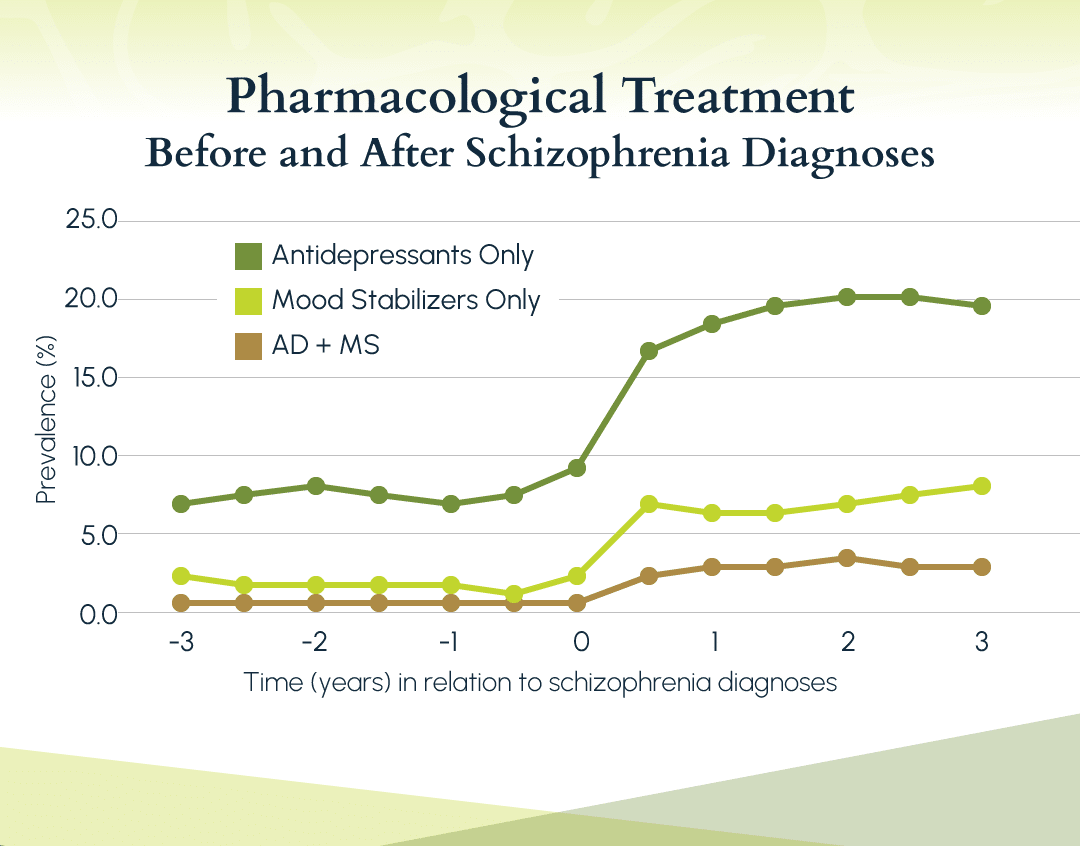

Depressive symptoms are a major component of schizophrenia, with some studies suggesting that more than 75% of patients have signs of depressive disorder before their first episode of psychosis. These can continue even long after psychotic symptoms fade, well into treatment for schizophrenia. Antidepressants are therefore a common component of most treatment plans, helping the client focus on developing the skills they need to function, instead of the symptoms of depression.

Antidepressants are often recommended if depressive symptoms continue after antipsychotic medications have been prescribed. However, evidence is mixed as to whether or not antidepressants are effective for overall outcomes. Psychosis and other symptoms of schizophrenia can worsen when antidepressants are added to a pharmacological mix, and even positive outcomes vary greatly.

Dr. Aminzadeh suggests a nuanced approach. “Antidepressants are a fantastic tool, when the situation calls for it,” he says, “Antidepressants can be critical, especially as that initial crisis phase ends. Once their psychosis resolves, many teens begin to learn about their condition, and realize that they will likely live with it for years. At that point, depression can really sink in. That post-crisis time period is a very high risk time for suicide.”

Mood Stabilizers

Mood stabilizers are a somewhat controversial complement to treatment for schizophrenia. While their application continues to help minimize affective and mood-related symptoms, the evidence remains inconclusive on their effectiveness.

“Well, I would prefer them on antipsychotics,” Dr. Aminzadeh says, regarding the pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia. “If a teen has a mood disorder, that’s when you will really see mood stabilizers play a role. First, you treat with antipsychotics and go from there.”

However, he continues, “But there are instances where we have used mood stabilizers in some cases for schizophrenia, even without comorbidity of mood disorders, to address fluctuations in mood or behavior. And it helps.”

Indeed, mood stabilizers remain popular treatment options with clinicians. Up to 1-in-4 patients receive them as part of their treatment for schizophrenia, and evidence suggests they lead to positive results.

From a 2020 study on the use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers with antipsychotics.

Mood stabilizers act as modulators for aggressive behaviors, with lithium treatments being particularly effective. Other studies have found that mood stabilizers reduce admissions for psychosis by more than 10%, though more research is required to see if this will continue over time. Other, adjacent medications, like benzodiazepines, are often prescribed in tandem.

However, it is worth noting one concerning trend in this area. Evidence suggests that the worse the long-term prognosis, and the more severe the individual’s symptoms, the more likely they are to be prescribed mood stabilizers – and the higher the dose of those prescriptions. Evidence does not support that this improves outcomes any further. This suggests the prescription of mood stabilizers may be to mitigate problematic emotional outbursts, rather than to treat their underlying causes.

Psychosocial and Behavioral Treatments

Many treatment plans focus on antipsychotic dosage, finding the right mix to reduce psychotic and psychosocial symptoms over weeks or months. And this is important! However, it is critical to combine this with long-term and coordinated therapies. Particularly for teens, whose schizophrenia will often be early-onset, combining therapy with pharmacological treatments boosts recovery rates, reduces the risk of relapse, and improves many quality of life metrics. Teens are also at particular risk of stopping their medication and leaving treatment – therapy can keep them in their treatment much more consistently.

Therapies, like their pharmacological counterparts, fall into a set of categories. We will focus on three: cognitive-behavioral therapy, skills training, and family intervention.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has proven to be one of the most effective treatments for the symptoms of schizophrenia. In particular, those symptoms that are resistant to treatment with antipsychotics – such as negative affect, or poor social skills and connection – can be addressed through cognitive-behavioral frameworks. Additionally, CBT can provide effective tools for addressing comorbidities, such as anxiety or mood disorders.

“It honestly varies a lot,” says Dr. Aminzadeh. “We’ve had patients who resonate much more strongly with CBT, who can’t tolerate the less concrete aspects of things like dialectical therapies. They love the manualized aspects of CBT. But it varies. That’s why it’s critical to assess each patient on their own merits. We usually find that a combination of these therapies, alongside antipsychotics, is most effective.”

Skills Training

Skills training is another highly effective treatment modality, reducing symptom intensity and duration, negative affect, and psychopathology. It does this while improving several other key areas, such as quality of life and independence. Further, evidence suggests that episodic relapse is less common in those who complete clinical skills training. A close cousin to the concrete aspects of cognitive-behavioral therapy, in skills training the goal is to build and strengthen a foundation for daily life.

These skills can include better coping mechanisms for emotional outbursts and handling psychopathological symptoms, practice expressing empathy and other emotions, as well as abilities important for day-to-day living. Schizophrenia can be highly disruptive to daily life, but by practicing these skills, individuals can begin to reclaim these parts of their lives.

Family Intervention

Family intervention – and by extension family education – is among the most potent treatment modalities. Studies point to immense improvements in outcomes, with the rate of relapse being reduced by more than 50% through family interventions. These interventions often focus on psychosocial education, emphasizing healthier emotional environments and communication methods. However, some key elements include schizophrenia-specific education, such as the importance of long-term planning and medication management.

“If an adolescent is diagnosed with schizophrenia, parents need to be involved immediately,” Dr. Aminzadeh says. “After that initial crisis phase is over, we like to sit the parents down and plan for at least 5-10 years out.”

He pauses before continuing. “We often recommend they consider conservatorship, so they have control and can ensure their kid receives the help they need down the road. It’s a hard conversation, but it always improves outcomes. That component of education, especially for families, is crucial.”

Conclusion

Schizophrenia is a complex and life-changing illness. While recovery is possible, a majority have lifelong symptoms. These can derail lives, leaving previously healthy individuals a shadow of who they once were. This serious mental health disorder is only exacerbated when it happens to an adolescent.

There are many challenges when it comes to teenage schizophrenia. How can you properly diagnose them? Teens are far more likely to exhibit non-schizophrenic psychotic symptoms and often have comorbid disorders that can be conflated with schizophrenia. What treatments are most effective? Most clinical work has been done with adults, and studies on adolescents typically end with “more research needed”.

Teens are particularly vulnerable to many symptoms of schizophrenia. They exist at a point in life where their rebellious urges to reject authority intersect with behavioral and psychotic symptoms pushing them to isolate, avoiding friends, family, and medication. Effective diagnosis can be challenging even under the best of circumstances, and when a teen is living with these symptoms, it becomes even more difficult.

If you know a teen who may be experiencing symptoms of schizophrenia or psychosis, know that hope is available. At BNI, a teen treatment center, our experts specialize in teenage and adolescent schizophrenia, as well as other psychological disorders. The earlier a teen is in treatment, the faster they will be able to be properly diagnosed, treated, and have their feet back on the path toward their future. Connect with us today at (888) 522-1504 to learn more about our world-class treatment options.

BNI Treatment Centers: Science-based, evidence-backed, compassion-led.

References

Abaoglu, H., Mutlu, E., Ak, S., Aki, E., & Anil Yagcioglu, E. (2020). The effect of life skills training on functioning in schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.5080/u23723

Amminger, G., Henry, L., Harrigan, S., Harris, M., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Herrman, H., Jackson, H., & McGorry, P. (2011). Outcome in early-onset schizophrenia revisited: Findings from the Early Psychosis Prevention and intervention centre long-term follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research, 131(1–3), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.009

Blum, R. W., Lai, J., Martinez, M., & Jessee, C. (2022). Adolescent connectedness: Cornerstone for Health and Wellbeing. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-069213

Breaux, R., Cash, A. R., Lewis, J., Garcia, K. M., Dvorsky, M. R., & Becker, S. P. (2023). Impacts of COVID-19 quarantine and isolation on adolescent social functioning. Current Opinion in Psychology, 52, 101613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101613

Budisteanu, M., Andrei, E., Linca, F., Hulea, D., Velicu, A., Mihailescu, I., Riga, S., Arghir, A., Papuc, S., Sirbu, C., Mitrica, M., Docu‑axelerad, A., Ghinescu, M., Dobrescu, I., & Rad, F. (2020). Predictive factors in early onset schizophrenia. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 20(6), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2020.9340

Etchecopar-Etchart, D., Korchia, T., Loundou, A., Llorca, P.-M., Auquier, P., Lançon, C., Boyer, L., & Fond, G. (2020). Comorbid Major depressive disorder in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(2), 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa153

Guo, X., Zhai, J., Liu, Z., Fang, M., Wang, B., Wang, C., Hu, B., Sun, X., Lv, L., Lu, Z., Ma, C., He, X., Guo, T., Xie, S., Wu, R., Xue, Z., Chen, J., Twamley, E. W., Jin, H., & Zhao, J. (2010). Effect of antipsychotic medication alone vs combined with psychosocial intervention on outcomes of early-stage schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(9), 895. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.105

Hahlweg, K., & Baucom, D. H. (2022). Family therapy for persons with schizophrenia: Neglected yet important. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 273(4), 819–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01393-w

Hjorthøj, C., Compton, W., Starzer, M., Nordholm, D., Einstein, E., Erlangsen, A., Nordentoft, M., Volkow, N. D., & Han, B. (2023). Association between cannabis use disorder and schizophrenia stronger in young males than in females. Psychological Medicine, 53(15), 7322–7328. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291723000880

Jablensky, A. (2000). Epidemiology of schizophrenia: The global burden of disease and disability. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 250(6), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004060070002

Jameel, H. T., Panatik, S. A., Nabeel, T., Sarwar, F., Yaseen, M., Jokerst, T., & Faiz, Z. (2020). Observed social support and willingness for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, Volume 13, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s243722

John, A., Gandhi, S., Prasad, M. K., & Manjula, M. (2021). Effectiveness of IADL interventions to improve functioning in persons with schizophrenia: A systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(3), 500–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211060696

Kelleher, I., Connor, D., Clarke, M. C., Devlin, N., Harley, M., & Cannon, M. (2012). Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1857–1863. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291711002960

Kelleher, Ian. (2023). Psychosis prediction 2.0: Why child and adolescent mental health services should be a key focus for schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Prevention Research. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 222(5), 185–187. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.193

Langman-Levy, A., Johns, L., Palmier-Claus, J., Sacadura, C., Steele, A., Larkin, A., Murphy, E., Bowe, S., & Morrison, A. (2022). Adapting cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescents with psychosis: Insights from the managing adolescent first episode in Psychosis study (maps). Psychosis, 15(1), 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2021.2001561

Leucht, S., Arango, C., & Lopez-Morinigo, J.-D. (2022). Pharmacological treatment of early-onset schizophrenia: A critical review, evidence-based clinical guidance and unmet needs. Pharmacopsychiatry, 55(05), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1854-0185

Molstrom, I.-M., Nordgaard, J., Urfer-Parnas, A., Handest, R., Berge, J., & Henriksen, M. G. (2022). The prognosis of schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression of 20-year follow-up studies. Schizophrenia Research, 250, 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.11.010

National Health Service. (n.d.). Causes – Schizophrenia. NHS choices. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/schizophrenia/causes/

Padma, T. V. (2014). Developing countries: The outcomes paradox. Nature, 508(7494). https://doi.org/10.1038/508s14a

Puranen, A., Koponen, M., Tanskanen, A., Tiihonen, J., & Taipale, H. (2020). Use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers in persons with first-episode schizophrenia. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 76(5), 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02830-2

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). Table 3.22, DSM-IV to DSM-5 schizophrenia comparison – impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and health – NCBI bookshelf. Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519704/table/ch3.t22/

Twenge, J. M., Haidt, J., Blake, A. B., McAllister, C., Lemon, H., & Le Roy, A. (2021). Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 93(1), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.006

Vita, A., Barlati, S., Bellomo, A., Poli, P. F., Masi, G., Nobili, L., Serafini, G., Zuddas, A., & Vicari, S. (2022). Patterns of care for adolescent with schizophrenia: A Delphi-based consensus study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.844098

World Health Organization. (2022). Schizophrenia. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia

Zhang, M.-D., & Mao, Y.-M. (2015). Augmentation with antidepressants in schizophrenia treatment: Benefit or risk. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 701. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s62266